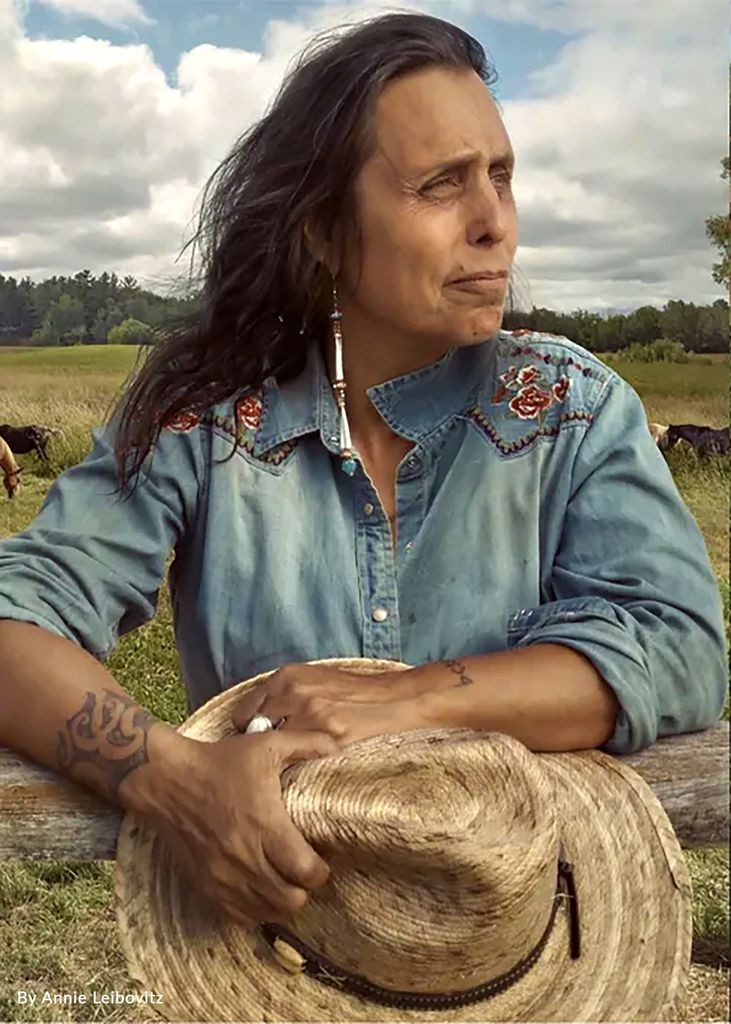

Winona LaDuke, a Native American activist, economist, and author, has devoted her life to advocating for Indigenous control of their homelands, natural resources, and cultural practices. She combines economic and environmental approaches in her efforts to create a thriving and sustainable community for her own White Earth reservation and Indigenous populations across the country.

LaDuke attended Harvard University and graduated in 1982 with a degree in rural economic development. While at Harvard, LaDuke’s interest in Native issues grew. She spent a summer working on a campaign to stop uranium mining on Navajo land in Nevada, and testified before the United Nations in Geneva, Switzerland, about the exploitation of Indian lands.

After Harvard, LaDuke took a position as principal of the reservation high school at the White Earth Ojibwe reservation in Minnesota. She soon became involved in a lawsuit filed by the Anishinaabeg people to recover lands promised to them by an 1867 federal treaty. At the time of the treaty, the White Earth Reservation included 837,000 acres, but government policies allowed lumber companies and other non-Native groups to take over more than 90 percent of the land by 1934. After four years of litigation, however, the lawsuit was dismissed.

The lawsuit’s failure motivated LaDuke’s ensuing efforts to protect Native lands. In 1985, she helped establish and co-chaired the Indigenous Women’s Network (IWN), a coalition of 400 Native women activists and groups dedicated to bolstering the visibility of Native women and empowering them to take active roles in tribal politics and culture. The coalition strives both to preserve Indigenous religious and cultural practices and to recover Indigenous lands and conserve their natural resources.

In 1989, LaDuke completed a master’s degree in community economic development at Antioch University. That same year, she founded the White Earth Land Recovery Project (WELRP), using funds the Reebok Foundation awarded her for her human rights work. WELRP is an organization that seeks to buy back reservation land previously purchased by non-Native people to foster sustainable development and provide economic opportunity for the Native population. It is now one of the largest reservation-based nonprofits in the country.

WELRP’s sustainable development initiatives include renewable energy efforts, indigenous farming and local food systems, and improved sanitation measures. They use the land they buy to generate wind energy; they have helped protect the local wild rice crop from patenting and genetic engineering; they encourage the consumption of traditional foods to combat rising rates of Type 2 diabetes in the community; and they run a diaper service that saves money and alleviates waste from disposable diapers. The organization raises money through the sale of traditional crafts, jewelry, and food to fund these programs.

Though busy with the WELRP, LaDuke continued her advocacy work with the Indigenous Women’s Network. In the early 1990s, LaDuke arranged a national concert series with the musical group Indigo Girls to raise awareness among young people about Native issues. In 1993, LaDuke and the Indigo Girls co-founded Honor the Earth, an advocacy and fundraising group that works on behalf of Native environmental organizations. Honor the Earth has granted over two million dollars to more than 200 Native American communities since its founding.

LaDuke has received many honors for advocacy work. In 1994, Time magazine named her one of the Fifty Leaders for the Future. In 1998, Ms. Magazine named her one of their Women of the Year. In 2015, she received an honorary doctorate from Minnesota’s Augsburg College and in 2017, LaDuke won the University of California’s Alice and Clifford Spendlove Prize in Social Justice, Diplomacy and Tolerance.

LaDuke has authored and co-authored numerous books concerning issues facing the Native American community. Her work Native Struggles for Land and Life (1999, reprinted 2016), for instance, tells of Native resistance to cultural and environmental threats.

LaDuke stepped down as the executive director of the White Earth Land Recovery Project in 2014 but continues to fight for Native Americans’ environmental interests. She was a leader at the 2016 Dakota Access Pipeline protests that sought to protect water access and sacred Indigenous lands in North Dakota. Today, the mother of six grown children (three biological and three adopted) devotes much of her time to farming. Located on the White Earth reservation, her farm grows heritage vegetables and hemp. LaDuke tries to publicize hemp’s environmental advantages: it requires less water to grow than cotton; can replace petroleum-based synthetics in clothing and other products; and absorbs carbon from the atmosphere, rather than releasing it.